Silhouettes: A Portrait Alternative with a Dark History (pun intended)

For hundreds of years, until the invention of the camera, the only quick and cheap method of immortalizing a loved one was through a shade, also referred to as a shadow portrait. As opposed to more decorative and expensive forms of portraiture like painting or sculpture, a shade was a simple and inexpensive alternative readily available for the common person.

Early artisans could copy a person’s profile using no more than scissors on paper and their two eyes, creating within minutes a freehand miniature in startling accuracy. These simplest methods were either–

- A “cut and paste” silhouette wherein the hand cut profile was pasted onto a contrasting background

- A “hollow-cut” created by cutting the profile from the center of a piece of paper and mounting onto a contrasting background. The example below is of the hollow-cut type, this from 1783 and of American President George Washington. Interestingly, it was crafted by Sarah De Hart, one of the earliest recorded female silhouettists in the USA.

Other silhouette methods were to paint with soot or lamp black onto plaster or glass. Casting shadows onto paper with lights was another technique utilized, referred to as an engraved or etched print. The artist traced the shadow and depending on his/her talent and the financial offering of the client, would cut from fine materials or add elaborate details. While more technical and requiring advanced skill as well as pricier materials, these two types of silhouettes were still far cheaper than a color painted portrait.

Staying with the theme, the silhouette below is also George Washington. This one is an engraved print by Johann Friedrich Anthing, published in his “Collection of 100 silhouettes” in 1791. Note the added details to the silhouette below, yet also take note of how perfectly both silhouettists captured President Washington’s profile.

Being an inexpensive artistry did not halt tracing shadow profiles from becoming all the rage in early 1700’s Europe. In France, the aristocracy embraced the amusement. Featured artists would attend extravagant balls and cut out the distinguished profiles of the Lords and Ladies capturing the latest fashions and elaborate wigs. In a strange twist of irony, it was this thrifty art form taken to incredible extremes by the pre-Revolutionary French noblemen and women that would later give the tracing of shades its perpetual name.

While the aristocrats were having their profiles cut out and eating like kings, much of Europe was starving. In the 1760s, the Finance Minister of Louis XV, Etienne de Silhouette, had crippled the French people with his merciless tax policies. Oblivious to his people’s plight, Etienne was much more interested in his hobby of cutting out paper profiles. He was so despised by the people of France that in protest the peasants wore only black to mimic his black paper cutouts. The saying went all over France, “We are dressing a la Silhouette. We are shadows, too poor to wear color. We are Silhouettes!”

The name “silhouette” in relation to shades would not be commonly used for another forty years, and it is essential to point out that Etienne de Silhouette was not the inventor of the art form, but the craft of profiling in shadow proliferated during his tenure. Thankfully the negative connotation linked to his surname did not last. Nor did the plain, unadorned black sketches he was known for.

Clients wanted novelty and artists needed to stand out from competitors. This soon led to elaborate variations on the simple cut profile. By the 1790s, many profiles were painted – on paper, ivory, plaster, or even glass. Elaborate embellishments became prominent, depicting jewelry, lace collars, and elaborate hairstyles. Bronzing, or the process of adding fine brushes of gold paint to the hair or clothing, became very popular after 1800. As briefly noted a few paragraphs above, increasing materials meant the price for a silhouette also increased. Yet more troublesome (at least to some) than the price was the line between what was a true “shadow portrait” or silhouette, and a portrait. More on that in a moment.

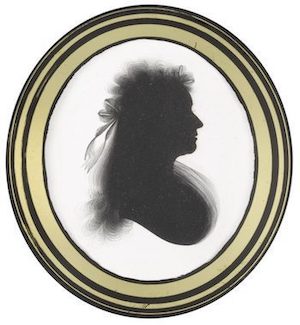

While some shades were proportional, or nearly so, most were very tiny. Placing the shadowy profile of a loved one onto a brooch or necklace required a skill of astounding proportions. Two of the most gifted in miniature silhouettes were Englishmen John Field and John Miers. Miers opened a London business in 1788, and attained a high level of success and fame including the honor of painting King George III and Queen Charlotte. Below are two of many surviving examples of his work, each showing his varied techniques.

John Field was originally Miers’ apprentice and later his partner of many years, inheriting the business when John Miers died in 1821. It is possible that many of John Miers’ later works were in fact executed by Field, which may explain the ring (above left) with the bronzed silhouette. Apparently, the bronzing technique was a feature of John Field’s personal style and was much criticized by John Miers, who felt that it was an unwarranted departure from the true shadow.

The locket below is a superb example of the finely executed bronzed work that was a hallmark of Field’s style.

The art of silhouette cutting reached its “golden age” in the 1800s. Many eighteenth-century silhouettists were, in fact, aspiring portrait artists or miniaturists. Some of them turned to creating silhouettes to tide themselves over when business was slack. Others found they developed a name for their work in this genre and quickly developed a market for it. Often unpretentious, they gave their public what they wanted without aspiring to artistic greatness, therefore reflecting with great clarity the pre-occupations and sensibilities of their time.

The most famous silhouettist of the Regency Era was Frenchman Auguste Edouart (1789–1861). He resisted the fancier flourishes, insisting on the traditional black outline, although his lithographed backgrounds are legendary for their beauty.

It was also he who first used the term “silhouette” formally, believing it had a magnificence to elevate the art form. Using embroidery scissors, he typically cut silhouettes by observing his sitters and moving the paper as much as his scissors, with his paper always folded to make duplicates (one kept for his personal portfolio). In 1814 he settled in England, traveling throughout the United Kingdom plying his artistry and becoming very wealthy in the process. In 1839 he sailed to America, where he traveled extensively for roughly nine years.

Among his patrons were America’s President John Tyler and ex-President John Quincy Adams, who mentioned Edouart when he wrote to George Washington in March of 1841.

“Mr. Edouart is a Frenchman … who cuts out profiles in miniature on paper, and came and took mine. … He took one also of my father from a shade taken in 1809, which with those of my mother, my wife, and myself, and our sons George [and John] then boys 8 and 6 years of age, we have under glass in one frame. He gave me a full-length profile of President Harrison, in the attitude of delivery his inaugural address.”

By the end of his life, it is estimated that he amassed a collection of over 100,000 silhouette portraits! On his way home in 1845, he boarded the Oneida, which wrecked in Vazon Bay, off the coast of Guernsey. The vast bulk of his portfolio was lost at the bottom of the sea, where they presumably still remain. Edouart escaped death but was so grief-stricken at the loss that he never again cut a profile.

The examples below, as opposed to the simplier self-portrait above, show his unique signature style.

With the advent of the camera and the increased availability of reasonably priced paints, silhouette as a unique art form waned by the end of the 19th century. After 1900, there were few artisans who maintained the professional attitude, and they were generally found at carnivals and seaside resorts. That is not to say, however, that the craft of silhouette died completely. Talented artists remain here and there, such as at Disneyland where our family has gotten silhouettes done several times (see two shadow portraits below).

[…] Silhouettes: A Portrait Alternative with a Dark History (pun intended) […]

I can understand that it might be quite easy to use the backlit projected image to produce a silhouette but to just draw or cut one out is amazing. I love yours!

Really neat! The one of your family is very pretty!

Thank you, Cindie! It is amazing how much the cutouts resemble us. Such an amazing skill.