Samhain = Halloween?

The origins of “Halloween” are steeped in mystery, vague references, superstitions, and suppositions. Personally I am not a fan of Halloween due to the death, terror, and general nastiness are at the center of the day. Enmeshing myself into that sort of stuff is not high on my list!

Despite my distaste for Halloween, honesty dictates that I admit the truth, this being that the “facts” of history are basically unknown and wildly contradict each other. After searching several dozen writings on the topic – religious, secular, and academic – with very few agreeing, this is what I can safely report….

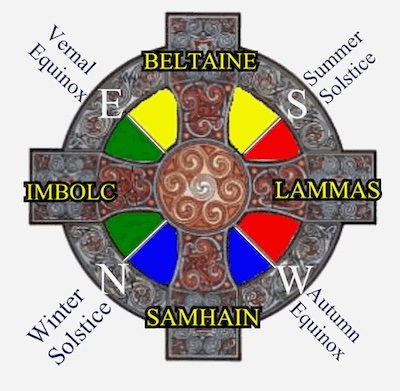

The Ancient Celtic people, who once were found all over Europe, divided the year by four major festival holidays. On their “calendar” the new year began on a day roughly corresponding to November 1st on our present calendar. As a pastoral people, it was a date marking the ending and a beginning of growth cycles. It was the change of seasons from growing, plenty, and life to winter, dark, shortages, and death.

The Ancient Celtic people, who once were found all over Europe, divided the year by four major festival holidays. On their “calendar” the new year began on a day roughly corresponding to November 1st on our present calendar. As a pastoral people, it was a date marking the ending and a beginning of growth cycles. It was the change of seasons from growing, plenty, and life to winter, dark, shortages, and death.

The festival observed at this time was called Samhain (pronounced Sah-ween) and meant “end of summer.”

Myth #1: The Celts were pagan with numerous gods, mostly of nature. True. What is false is that their “god of death” was named Samhain (or Samhan). No concrete evidence of this deity exists, and certainly not that the end-of-the-year festival was named for him.

While the precise nature of how Samhain was celebrated in ancient times is largely unknown, there is no doubt it was the most significant holiday of the Celtic year. The annual communal meeting at the end of the harvest year might have lasted for days, and may well have been similar to a US Thanksgiving feast. There were supernatural and religious aspects to the pagan festival, though nothing that would be considered sinister by modern standards. According to Nicholas Rogers, a history professor at York University and author of Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, “there is no hard evidence that Samhain was specifically devoted to the dead or to ancestor worship, despite claims to the contrary by some American folklorists.” Samhain, originally at least, was less about death or evil than about the changing of seasons and preparing for the dormancy (and rebirth) of nature as summer turned to winter.

Samhain Bonfire by Digimaree

Myth #2: The Roman Catholic Church created All Saints Day (All Hallows Day) and/or set it to November 1 to counteract the horrible pagan Samhain celebrations.

See my post on Monday detailing the origins of All Saints Day and the date selection. Some scholars believe that All Saints Day and Samhain, coming so close together on the calendar, may have influenced each other and combined into the celebration now called Halloween (from All Hallows Eve). This is nebulous at best. The truth is that a direct connection has never been proven. Two notable historians (of many) Ronald Hutton (The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain, 1996) and Steve Roud (The English Year, 2008, and A Dictionary of English Folklore, 2005), flatly reject the popular notion that the Church designated November 1 as All Saints Day to “Christianize” the pagan holiday. Citing a lack of historical evidence, Roud goes so far as to dismiss the Samhain theory of origin altogether. It is also important to note that by 500-600 AD the Celts, Gauls, Gaels, etc. had mostly been conquered and absorbed into other cultures, except for those Celts restricted to Ireland.

Myth #3: Celts worshipped the dead and sacrificed humans on Samhain to appease their gods.

I suppose anything is possible, but again there is nothing concrete that this was happening. Like many cultures of the past, the Celts were very superstitious. They deeply honored the intertwining forces of existence: darkness and light, night and day, cold and heat, death and life. Celtic knot-work represents this intertwining. They observed time as proceeding from darkness to light, their day beginning at dusk and ended the following dusk. Samhain, as noted in the first paragraph, was especially holy as the change from one year (or cycle of seasons) to the next, the ultimate dusk to dusk as it were.

In line with this idea, they believed it was a night with a gap in time and reality, where the physical world and the “Otherworld” came together. However, much like All Saints and All Souls Day for the Christian Church, it was a day of honor and remembrance, the big difference, of course, being the belief that the dead could return to the places they had lived. These returning spirits were not evil but relatives welcomed hospitably. Windows, doors, and gates were left unlocked to give the dead free passage into their homes where food and drink was left for them.

Myth #4: Druids delved deeply into sorcery, witchcraft, and other dark arts, and extensively performed human sacrifice.

Maybe to a degree, but probably not extensively. ALL of the sources describing the activities of the Druids come from the Romans. These writers, including Julius Caesar, are extraordinarily detailed in the atrocities committed just as they are for the other “barbarian” people conquered. The problem is little archeological evidence of human sacrifice by the Celts, suggesting the likelihood that Greeks and Romans disseminated negative information out of disdain or for political purposes. Archaeological evidence that does seems to indicate human sacrifice may have been practiced long pre-dates any contact with Rome.

Furthermore, according to historian Ronald Hutton, “we can know virtually nothing of certainty about the ancient Druids, so that—although they certainly existed—they function more or less as legendary figures.” What is known with relative certainty is that they were the religious leaders, law givers, judges, keepers of oral history, astrologers, and teachers. Did some of this include divination and other “magic”? Surely it did. How much or if “evil” in nature is the question. Without veering off into a separate dissertation on the Druids, I’ll simply say that the mysteries are too shrouded. Also, by the 7th century they had faded as a priestly sect and for the subsequent centuries held minimal influence other than as wise men.

In conclusion, as to this portion of the origins, Halloween as we know it today, while rife with strange rituals of a negative bent, isn’t absolutely, definitively tied to pagan Celtic rites. So what about bonfires and trick-or-treating? Come back tomorrow and I’ll cover what I can.

[…] Samhain = Halloween? […]

This paper is facinating. I feel you’ve covered a lot of ground in that which you’ve presented. The illustrations and observations concerning Greco-Roman influence say a lot. I imagine History is toughf subject and think you’re fairly just in mentioning that some of the ‘facts’ are mysterious. Thank you for taking the time to come up with some answers.

I don’t participate in Halloween “festivities”, as it were, and haven’t my entire life. I was raised in a Pentecostal preacher’s home and we discussed from the time I was very small, that whatever the origins of Halloween were, what it is considered today is what we do not support. =D My dad always gave a lesson on people taking advantage of a situation to promote black magic and evil. As an adult, though I’ve changed the religion I still don’t see Halloween as having any place in my life. This is really interesting info too: never ceases to amaze me how some nations or groups of people are villianized by their political opponents as part of the “game” and that the stereotype sticks.

Amen sister, that’s a real Celtic cross And the author does a nice presentation for what modern Readers may be curious towards concerning an ancient relic and related Language and culture.